How to Save Kirana Stores from Quick Commerce

Looking at consumption patterns of Indian grocery shoppers, it doesn't look like it's the traditional stores that need saving.

I was seven when the first supermarket opened in my hometown. It was around the time when Coca-Cola returned to India after nearly 15 years. Both these things together - the first supermarket and Coke's return - seemed to get the grown-ups excited. They'd never been too pleased about soft drinks or junk food. And so an unusual family outing was planned. There was a crowd outside the Coca-Cola stall. My parents even ran into some friends and their kids, which made it all the more weird - a supermarket wasn't the kind of place where elders met for a get-together. I remember feeling really disappointed at my first bottle of Coke. I'd had soda before, but this one tasted like shit. I had yet to discover the link between fried, salty food and carbonated drinks. But everyone else, especially the elders seemed to like it. So I pretended to like it too.

I grew fond of the supermarket, as it slowly replaced the neighbourhood grocery store. I forgot the name and the face of the local grocer, who was fast approaching the designation of "my grandfather's grocer". Supermarket visits were exciting because it was fun to push the shopping cart. It was easy to sneak packets of chocolate and potato wafers into the cart. They'd be discovered only at checkout, by which time a parent would be too hassled to not buy it.

Today, the only time I go to a grocery store is if I'm visiting something near one. I've stopped going to supermarkets too - I'm completely dependent on BigBasket and Blinkit. What's really surprising is that my parents use these apps too. When they first visited me in Delhi, one of the first things they asked me was directions to the nearest grocery store. I didn't know what to tell them. Their eyebrows disappeared when I told them where the groceries really came from.

"Even the fruits, vegetables, milk and eggs?!"

"Yes."

"How do you know they're not stale?"

"Well, as long as they don't stink..."

They gave each other the hopeless look that all children know so well.

I come from a long line of late adopters. Simon Sinek described late adopters as the people who'd only buy a touch-tone phone because nobody would repair a rotary phone. That's exactly who my parents were. But now, post-COVID, they're different people. They're older, they've lost some of their mobility, and their sons don't feel too enthusiastic pushing carts down the supermarket aisle. Now, they are quicker to use Blinkit than me. My mother even talks about instant delivery apps as if she discovered them.

If a bunch of apps can change my mother's shopping habits - they can do anything.

In the past year alone, we have enough evidence of e-commerce changing the market. In 2024, Swiggy went public, Zepto raised half a billion dollars, and Flipkart and Bigbasket started operating in a visibly better manner. In April 2024, Blinkit announced that they'd deliver a PlayStation 5 in ten minutes. To me the idea was outrageous. As anyone from the erstwhile pre-liberalisation middle class knows, buying expensive items is a ritual. Buying costly appliances in just ten minutes - without months of research and penny pinching - is just disrespectful.

I asked a lot of people about the most expensive thing they'd bought off an insta-delivery app. I couldn't find anyone who'd spent more than a few thousand rupees. A few people said they'd ordered protein powder or a video game controller or a game (not the console itself). Relatively the most expensive item I encountered was a UPS my wife bought for her office.

But who would actually need a PlayStation delivered in ten minutes?

I spoke to Deepak "Chuck" Gopalakrishnan about this. According to him, extravagant offers are more marketing signals than revenue drivers - if someone claims they can deliver gaming consoles in ten minutes, then they can certainly deliver groceries in time. Perhaps, it takes signals like these to reach late adopters like my parents. Many other customers like myself will sell their loyalty to a brand for a lot less. Quick commerce to me is no longer a luxury, but an unequivocal default, a habit.

So when someone on LinkedIN said that e-commerce apps are destroying traditional kirana stores, I wasn't surprised. On the contrary, I was sympathetic. The post claimed that nearly 2,00,000 kirana stores had shut down in the last year because of the 'predatory' practices of e-commerce companies. That's not a small number. It means that the lives of at least 2,00,000 proprietors have been affected - not to mention those of their staff and families. It won't be a stretch to say that at least a million people could have been affected by this, either directly or indirectly.

But in a swift change of tone, the post went on to offer some solutions which, at best, seemed like a rehash of management consulting jargon, and at worst, sounded condescending. The post suggested that kirana stores can bridge the gap with "tech integration", "omni-channel presence", "customer experience", "training and upskilling", etc. Not only does this sound disingenuous by itself, but when used in the context of grocery stores, it also comes across as downright unprincipled. I wish someone would say these phrases out loud in a kirana store and record the reactions. The post was clickbait to begin with. The caption had the words "SHOCKING DATA" in the thumbnail, in a large font, complete with the picture of an old man sitting behind the counter of a customer-less store - only his face visible between jars of confectionery and overhanging packets of chips.

Clearly, something was being sold to the reader. When a less-than-sincere sale is coupled with clickbait, there's always something interesting under the hood.

Under the Surface

The OP had cited no sources, even though they were a quick Google search away. In October 2024, the All India Consumer Products Distributors Federation (AICPDF) reportedly wrote to various government bodies, including the Competition Commission of India (CCI), complaining of the (allegedly) predatory practices of e-commerce companies. Their letters or press releases aren't directly available, but many media outlets have independently reported their claim of 2,00,000 kirana stores shutting down in the last year. It's safe to say that this entire discussion stems from an unverified claim.

But when we read the details of this claim, the picture becomes less bleak. The country apparently has 13 million kirana stores. So 2,00,000 of them shutting down is a 1.5% reduction. Further, if we were to limit the numbers only to metros, the closure rate rises only up to 5%. It would be tempting to think that this is a small fraction, but that may be a mistake, since we don't know what the usual rate of closures under healthy market conditions is - we don't know what the default benchmark is. It's quite likely that the OP is right, and that 5% kirana stores shutting down in metros is indeed "SHOCKING DATA".

But the claim that this is happening solely because of e-commerce companies is certainly not beyond reasonable doubt. So I went looking for something that would help me find the general, average success rates of kirana stores.

Sadly, I could find no such resource. What I did find was that kirana stores are no strangers to threats from e-commerce.

There are enough reports dating back to the 2010s which show that there have been concerns about supermarket chains damaging Kirana stores (it was the heyday of Big Bazaar and D-Mart). Then in the late 2010s, Amazon and Flipkart became a concern, but they didn't manage to displace more than 1-2% of local stores. Even when the lockdown came, e-commerce managed to displace about only half a percent of kirana stores. In this light, it's reasonable to assume that while the figure of 2,00,000 looks big - it's certainly not an outlier. It is also noteworthy that as much as there is concern towards e-commerce, there are also stories of the triumph of kirana stores! PhonePe claimed, in 2021, to have digitized 25 million "kirana stores and small merchants."

By now it's clear that grocery stores have survived many threats. In business (especially one as price-sensitive as FMCG retail) as well as in technology, nearly every decade brings a new supposed threat. Morgan Housel wrote in is book, Same as Ever, "It's good to always assume the world will break about once per decade, because historically it has."1 But decade after decade, kirana stores seem to have been remarkably resilient.

But no matter how much of a threat or opportunity anyone may believe e-commerce to be, the discourse so far has been purely theoretical - based only on claims, counterclaims and conjecture. There are bigger issues to resolve, like identifying the true impact of e-commerce on grocery shopping. To answer this, we turn to the Household Consumption and Expenditure Survey (HCES).

Digging Deeper

HCES 2023-24 was conducted between August 2023 and July 2024. The survey interviewed nearly a million individuals across almost 2,50,000 representative households2. A major part of the survey deals with groceries3, including some auxiliary information on payment methods and use of welfare schemes.

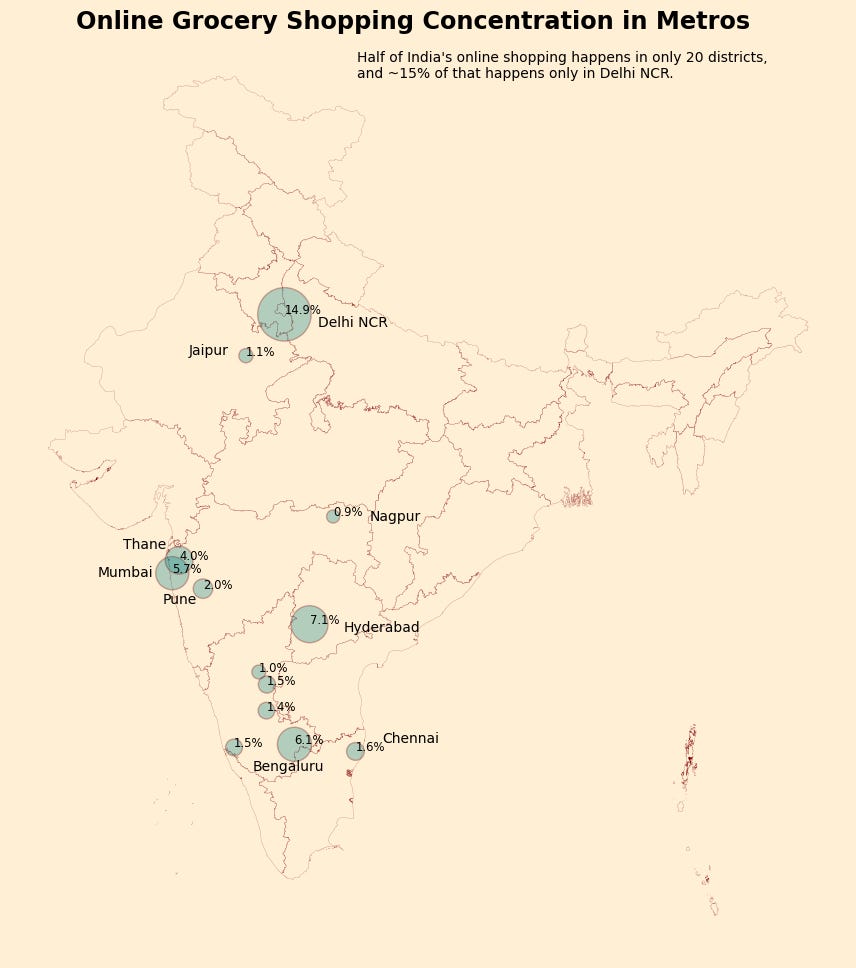

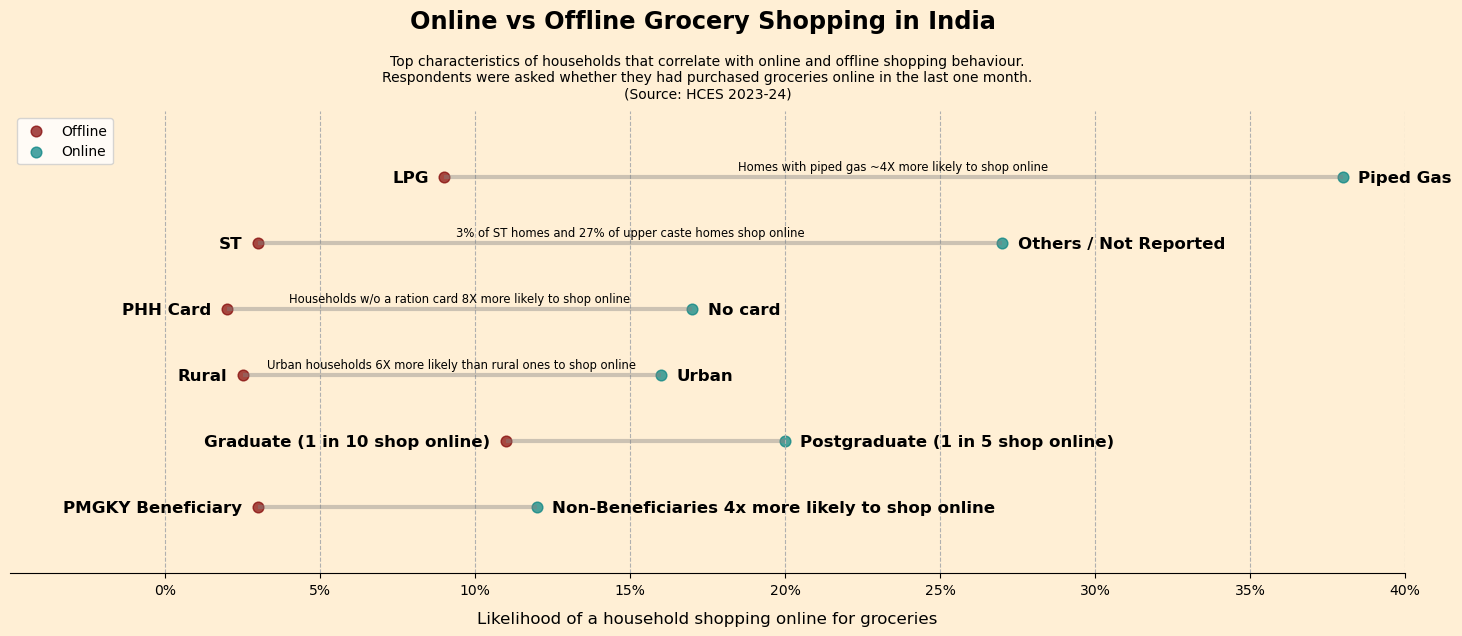

It is only in the context of the HCES microdata that I found the caption "SHOCKING DATA!" to be truly justified. For instance, only 7% of households in the country shop online for groceries!4 And of those households, more than half are located in metros and a few Tier-I cities, across only four states.

Online grocery shopping is a predominantly urban phenomenon, and saying even that is a stretch. A whopping 83% of even urban households don't shop online! Recall AICPDF's claim of 5% of kirana stores shutting in metros. The numbers are far too lopsided on the side of traditional grocery shopping to consider e-commerce as a serious threat. Other than traditional grocery stores, the survey also contains details of other ways in which consumers can procure groceries, like subsidized rations, the Public Distribution System and the Pradhan Mantri Garib Kalyan Yojana.

In short, simply shopping online or offline for groceries, with cash or with UPI isn’t the end of the story. The survey reveals such a great diversity in what and how Indians eat, that it's almost impossible to pinpoint the habits of an average Indian grocery shopper. For those of us who, like Amit Tandon says, order the bread after they break the eggs, who instinctively look for a QR code whenever we buy something from a brick-and-mortar store, it's impossible to imagine who the "offline consumer" really is.

The HCES allows us to divide the respondents into cohorts of online and offline shoppers. The imbalance between the sizes of these cohorts is staggering (7% online vs 93% offline!), but when we adjust for size, we find some significant markers of difference. For example, living in a home which has access to piped cooking gas makes you four times more likely to shop online than if you cooked with firewood, biogas or even LPG. When we move from the cohort of graduates to postgraduates, the odds of finding online shoppers are doubled.

In this light, the conflict between e-commerce and kirana stores seems to be insignificant. In fact, it seems like the real conflict is between e-commerce and lack of urban infrastructure, lack of quality education and massive income inequality.

Consider this: if e-commerce can target no more than 7% of Indian households, and if most Indians have no discretionary spending power - then who's the one who is really in trouble?

Certainly not the kirana store.

The well meaning folk who urge traditional stores to "bridge the gap" with "tech integration" and "omni-channel presence" might be better off directing their wisdom elsewhere.

Zooming Out

Even with all the number crunching, we're still looking at consumers simply as weighted sums of statistical attributes. The real Indian consumer still remains elusive, if there even is such a thing. The common consumer, then, becomes a mere metaphor in public discourse.

The Marathi movie Half Ticket shows such a metaphor. It's a story of two young slum-dwellers who steal eggs from crows' nests, because they can't afford chicken eggs. The park from where they get these eggs is sold off and turned into a pizza joint. The kids then get obsessed with eating a pizza. They work odd jobs for weeks, trying to save up the 300 rupees for a pizza. Finally when they're ready to order one, they realise that it can't be delivered to their home, because their address is simply the name of the jhuggi where they live. They have no house number and no street name5. When they visit the store, they're humiliated and thrown out because of their appearance. They go back to work and save more money to buy better clothes. When they return to the store they're thrown out once again - the guard knows they are slum dwellers. The movie does have a happy ending, the kids do get their pizza, but only because someone thinks that feeding a couple of poor kids is good PR. They have baggage that, even with money and clean clothes, cannot be jettisoned.

It's like there's an entirely different country living within India. I myself am squarely in the 7%, and there's a whole world out there which I'll never see, no matter how hard I look.

But I certainly wouldn't presume to sell anti-e-commerce solutions to kirana stores. Much less on social media of all places, with clickbait and alarmist captions.

Note: The HCES datasets, their analysis and the code used to generate the visuals here are available for scrutiny and reuse. Please leave a comment if you'd like to get your hands on them.

Housel, Morgan. Same as Ever - Harriman House, 2023, p. 109

In the HCES, items that fall under groceries are: cereals, pulses & their products, edible oil, sugar & salt, spices, beverages, milk and milk products, vegetables, fresh and dry fruits, egg, fish and meat, served processed food, packed processed food and other food items.

The households selected for the survey are representative, and each sample has a weight that is a measure of it's importance in the overall survey. All figures inferred from the survey are weighted metrics.

Neil Postman wrote, “… embedded in every tool is an ideological bias, a predisposition to construct the world as one thing rather than another…” CRMs in restaurants must necessarily record your address in multiple fields, all mandatory. For the CRM, there cannot exist a spot of land which is not defined by these few address fields.

In one of his myth-busting videos, Krish Ashok talks about how thousands of Indians who are actually rich believe they are middle-class because the gap between the rich and the super-rich is so stark. Living in gated communities inside metros, working in fast-growing companies, being online all the time, valuing time and convenience over anything else, we have no idea that any other kind of life is even possible. Because we haven't shopped from a local kirana store in many years, we believe reports that say nobody shops from kirana stores. (We may still not do anything to change our habits or support these kirana stores in any way, except perhaps write a tweet thread about it.)

I love the whole idea behind this newsletter, to examine all kinds of data to evaluate whether a popular or even a controversial piece of news is really true. Looking forward to more!

P.S. Half Ticket is a remake of the critically acclaimed 2014 Tamizh film Kakkamuttai (Crow's Egg).

There was a Matt Yglesias post about big retailers being more productive and better employers than mom-and-pop stores, which led me to binge-read about Kirana stores in India. I too found those fear-mongering "Kirana stores aren't gonna make it" articles from the early 2010s. And I concluded that much of it was overblown, given that it was impossible for online delivery apps to penetrate every nook and corner of India and have the personal touch of your neighborhood mom-and-pop store.

Not just that, the government did launch the ONDC scheme so mom-and-pop stores could have a level playing field, but idk how it's working out.